Jan Mayen information

On this site, you will find an introduction to the fascinating island of Jan Mayen, including the following sections:

General: Jan Mayen is situated at 71°N/8°W or, in other words, about 550 kilometers north of Iceland and 450 kilometers east of Greenland. The land area is about 373 square kilometers, similar to La Gomera in the Canary Islands or the Lake Garda in north Italy. The shape is quite peculiar, similar to a narrow spoon, stretching 53 km long from southwest to northeast. This has to to with the geology – see next section below: Geology). The spectacular scenic centre point of Jan Mayen is the 2277 meter high glacier-covered volcano Beerenberg with its symmetrical cone shape.

Jan Mayen was discovered early in the 17th century and became part of Norway in 1930. There is an active Norwegian military and weather station. There is no touristic infrastructure whatsoever: no accommodation or transport facilities (neither from the outside world to Jan Mayen and back nor within the island) available to the public. In 2010, Jan Mayen was declared a Nature reserve – generally without any doubt a good thing, but restrictions for visitors are ridiculously strict, making it even more difficult to visit the island properly (see section Regulations). Tourist visits, already rare before 2010, have accordingly become even more scarce, especially those very few ones who did a bit more than visiting the station or Kvalrossbukta. Hard weather, rough seas and the lack of sheltered natural harbours make it difficult enough to visit Jan Mayen anyway. On the other hand, it is a unique, fascinating island, interesting with regards to geology, scenery and history, and absolutely worth seeing and experiencing for adventurous polar enthusiasts.

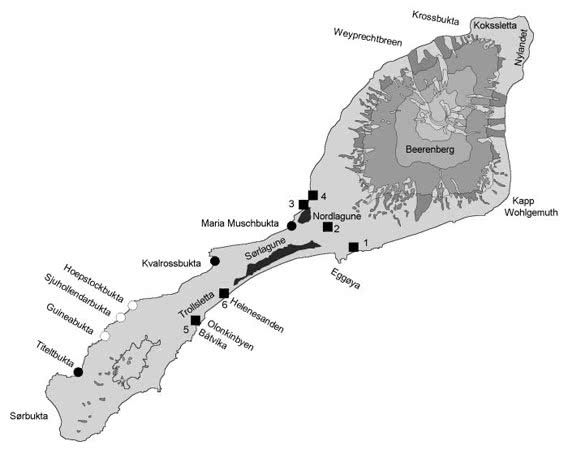

© Rolf Stange – Jan Mayen. The island is 53 km long (SW-NE) and just 2 km wide in the central part.

Black circles: 17th century whaling stations. White circles: 17th century whaling stations (assumed). Squares: Stations (1. Eldste Metten = weather station 1921-1940. 2. Jøssingdalen (weather station 1941-46 and garrison), 3. Atlantic City (US Coastguard station, 1943-46, weather station 1946-49) 4. Gamle Metten (weather station 1946-62), 5. Olonkinbyen (today’s Norwegian station, active since 1958), 6. Helenesanden (weather department of the station since 1962).

Breen = glacier, bukta = bay, Kapp = cape, Nylandet = New Land, sletta = plain, Vika = small bay.

Geology: Jan Mayen is geologically similar to Iceland, but completely different to other land masses and islands in the north Atlantic such as Norway, Greenland or Spitsbergen. It is even younger than geologically rather adolescent Iceland. Both are part of the middle Atlantic ridge system, but Jan Mayen is not situated exactly on top of it. The island is owing its existance and its peculiar shape to a so-called Hot Spot (talking plate tectonics, not wireless internet) and the fact that the plate with Jan Mayen on top is slowly drifting over the Hot Spot, which itself is deep-seated and stationary. The volcano Beerenberg is still active, with several eruptions during the 20th century. These took place not at the large central crater at the top, but near the northern tip of the island (Nylandet = new land).

Climate & glaciers. The climate is distinctly maritime-arctic. In other words, the weather is mostly pretty poor. Clear and cold winter weather is as rare as sunny summer days. Fog, wind and drizzle, not producing much precipitation but making you nevertheless quickly wet, are characteristic for Jan Mayen. The well-known Iceland low pressure system should actually be called the Jan Mayen low, because this is where it is from.

Precipitation is increasing with altitude, and so is the proportion of precipitation that falls as snow. This is why Beerenberg has more than 100 km2 of glaciers, 5 of which reach down to sea level. At least they did so until a few years ago; they are shrinking as they do almost everywhere and the only one that still has an impressive calving ice cliff is Weyprechtbreen, which is is descending down directly from the central crater at the top of the volcano. Spectacular stuff, indeed! Most of the other glaciers are more and more hiding under their growing terminal morains.

Currents & Ice. Jan Mayen lies within the area with different oceanic water masses meet. The East Greenland current brings cold water and huge masses of drift ice from the Arctic Ocean, following the coast of East Greenland down south. Coming from the southwest and bringing large masses of temperate water into the northeast Atlantic is the Gulf Stream. Jan Mayen is pretty much exactly on the boundary zone of these two, where arctic and temperate water masses meet and mix. Today, the cold waters of the East Greenland currents do rarely touch the shores of Jan Mayen anymore, and drift ice is hardly seen around the island. If so, it comes „normally“ some time between March and early May, but chances the ice comes as far east as Jan Mayen have become very slim these days.

Flora & Fauna. Jan Mayen’s fauna is mostly characterized by seabirds breeding on steep cliffs and slopes. Important species include the Northern fulmar, which is beautifully adapted to the harsh weather and open sea and may well be called a character bird of Jan Mayen and the surrounding ocean. Also very abundant are the Kittywake, Brünich’s guillemot and Little auk, the latter one breeding under rocks on steep slopes rather than on vertical cliffs. Birds typical for the arctic tundra such as the Snow bunting, Grey phalarope, Turnstone and others are hardly found on Jan Mayen due to the obvious lack of tundra vegetation and wetlands. There are no terrestric mammals since the Polar fox was driven to local extinction in the early 20th century. There have never been Muskoxen, reindeer or rodents. Polar bears may visit the island occasionally when there is drift ice around, but they haven’t been seen in recent years as the East Greenland ice does not reach Jan Mayen anymore.

The area is nevertheless biologically very rich, but it is the sea that is productive and has a lot of life, not the mostly very barren land. With some luck and calm weather, a number of whale species up to the very largest one, the Blue whale, can be seen, and several seal species feast in the rich fishing grounds.

What is mostly striking about the vegetation over large parts of Jan Mayen is its absence. Large areas are almost completely barren, dark plains of volcanic sand and rocks. Other parts have surprisingly rich, thick and colourful carpets of mosses and lichens. The list of vascular plants is much shorter than on Spitsbergen, which is much further north, and the species diversity of neighbouring Greenland reminds of a tropical reinforest in comparison, but it includes several species of saxifraga and even several dandelions, including endemic ones.

History. The early history of Jan Mayen is no more than legends if anything at all, and it may well be that no one has ever seen the island before the days of the whalers in the early 17th century. There are some stories of Irish monks in the 7th century followed by the Vikings, who certainly went from Norway to Iceland and further to southwest Greenland, but if they ever came anywhere near Jan Mayen remains unknown. No one less than famous Henry Hudson may have discovered the island in 1608, but the first confirmed sighting was made in 1614 by John Clarke from England. Clarke was soon followed by whalers who started to exploit the biological treasures of the arctic seas in the 17th century. Dutch whalers established several stations on Jan Mayen. A few remains can still be seen at two sites on the northern side of the island, including Kvalrossbukta. Jan Mayen obviously received its name in those years, commemorating a Dutch whaling captain. An attempt to winter during 1633-34 ended fatally: all 7 men died of scurvy.

Once the whales got scarce and whaling remained without profits, Jan Mayen mostly disappeared in northern mists again until it was visited the next time by a group of Austrian scientists during the First International Polar Year (IPY) in 1882-82. The Austrians established a station in Maria Muschbukta and were the first ones to winter successfully on Jan Mayen. The whole expedition was quite successful, „only“ one sailor of the transport vessel died of tuberculosis and was buried on the spot near the station (his grave is still there), the wintering crew returned home with a wealth of data as part of the international programme carried out in the Arctic and Antarctic during that first IPY.

Norwegian trappers discovered Jan Mayen in the early 20th century as a rich hunting ground for the polar fox. The first wintering of that period took place in 1906-07 and was initially a success: the trappers could board a small ship to bring them back home after a good season. But desaster struck near Iceland, when the ship sank and all except the machinist died. Several hunting parties wintered in following years, some of them returning back home with record catches of Polar fox, including a high proportion of the rare variety called Blue fox, which has darker fur which fetched good prices. Unfortunately, the local population of foxes could not tolerate the hunting pressure and collapsed soon. The Polar fox is still locally extinct on Jan Mayen, one can only hope that it will return to the island one day with the drift ice from East Greenland.

Progress within the field of meteorology and the need for reliable weather forecast made it necessary for Norway to establish a weather station on Jan Mayen. This was done in 1921. The station was re-located several times during the 20th century, but has been operated continuously since 1921 with the exception of the dark years of WWII. Run originally with 3, then 4 men, to begin with just north of Eggøya on the southern side, it also served as an important radio station for fishing and sealing ships. The earliest one near Eggøya is now generally referred to as Eldste Metten (oldest met(eorological) station).

Several attempts were made during the 1920ies by Norwegian individuals to take possession of Jan Mayen, and soon the Norwegian government, represented by the crew of the weather station, entered the scene. In 1930, a law came into force that declared Jan Mayen part of the Kingdom of Norway. But the ground was still private property of a Norwegian, who had persistently put up his annexation signs and went the weather station crew and Norwegian officials on the nerves, thus securing his claims both locally and in Norwegian courts. The government bought the island later from his descendants to achieve full control. Jan Mayen is accordingly now both Norwegian territory and state (not to be mistaken for „public“) property. The differences and factionalism related to the sovereignty and ownership question in the 1920s and 30s were in fact quite bizarre.

The Norwegian weather station was evacuated during early stages of WWII in September 1940, but re-established as soon as early 1941 at some distance from the coast because weather forecasts were important for the military on both sides. Also the Germans tried to establish meteorological aircraft (hydroplanes), but limited themselves to regular meteorological flights and weather ships from occupied Norway after some false attempts. Supported by the United Kingdom, Norway kept the weather station active in Jøssingdalen (see map above) and added a military garrison to „guarantee“ the safety of the station. Shots were occasionally fired from both sides when German aircraft flew over the station, but without any real damage or even loss of life on either side. But to German aircraft crashed into mountain slopes on Jan Mayen during the war years due to bad navigation. During later years of WWII, the US Coastguard established a station to detect and track down enemy radio traffic. The Americans and their station, called „Atlantic City“, were not far from their Norwegian neighbours, until they left in 1946 as agreed with the exiled Norwegian government in London. The Norwegians soon took over the buildings of Atlantic City and used them as their temporary weather station until 1949, when they built a new, better one just next door. The new station („Gamle Metten“, no 4 on map above) was fine, but very exposed to the occasionally violent winds that can fall down from the glaciated slopes of Beerenberg. Extreme wind conditions led to a tragic accident when station leader Aksel Liberg was simply blown away during an attempt to get to the meteorological instruments of the station. His frozen body was found days later, only 150 meters from the station buildings!

In the late 1950s, the Norwegian military built a station on the south side of the island, where it is still today. Its name is Olonkinbyen (Olonkin City), after a station manager who spent some years on Jan Mayen during the 20th century. The purpose of the station was to serve the military LORAN (Long range navigation) system, which one would think is obsolete in the days of GPS and rumours were that it was to be abandoned during the years after 2000, but the rumours have gone and the station is still there (to my knowledge, the LORAN function was put out of use in 2006, but the station and a crew of around 19 are definitely still there). In 1962, the weather station moved to the LORAN station, as it had to be rebuilt anyway and it made logistically sense to have one station rather than two. The weather station itself is, strictly speaking, shortly north of the actual LORAN station, close towards the runway, which is occasionally used by Norwegian airforce Hercules planes to supply the station, but it is not open for public use.

Regulations: Before I briefly summarize those parts of the regulations that came in 2010 (see below), I want to describe the situation until then and make some comments.

Until 2010, those few visitors who made it up to Jan Mayen could pretty much land anywhere, depending on wind, weather and sea (which meant that some did not land at all, others had to be happy with a few wet hours in Kvalrossbukta and some lucky ones made it to a number of interesting sites within a 1-2 day visit). F0r a few adventurous polar enthusiasts, it was logistically challenging but legally possible to land somewhere convenient to establish a base camp somewhere near Beerenberg to hike and climb up to the summit of the glaciated volcano crater, 2277 above the wave-hidden shores, to enjoy some magnificent views in a rare moment of clear skies.

In late 2010, however, the Norwegian government declared Jan Mayen a nature reserve, something that is generally to be welcomed in the days of the fishing and oil industry putting more and more pressure onto the remotest areas. But it remains a mystery why Norwegian authorities consider the miniature tourism on Jan Mayen a threat to the environment. One can only guess that nobody seriously does, the author of these lines is certain they simply don’t like it. Arguments given by relevant authorities during the hearing that was held before legislation finally came into force do hardly go beyond general and rather weird statements that Jan Mayen is a poorely understood ecosystem that needs accordingly to be protected from risks unknown (and hard to imagine, one might add) based on a precautionary principle. Of course also something that is certainly to be welcomed: don’t let bad things happen in the first place. The author finds it hard to argue against it. But the „precautionary principle“ is simply so over-stretched here that it cannot be described with any other words but ridiculous. What harm should be done by putting up a few tents for a few days on dark volcanic sand? What is the environmental benefit in not letting rare ship-based visitors go ashore on often driftwood-covered beaches to see, for example, the remains of the Austrian wintering station in Maria Muschbukta, or the small monument that was erected at Kokssletta to commemorate five English scientists who died during a boat accident in 1961. Of course, trampling boots may potentially cause harm to vegetation (where present) or historical sites, but experience from other polar areas such as Antarctica or Spitsbergen has shown that this can be done successfully without closing large areas down (although Norwegian authorities have in recent years started to implement similarly shizophrenic legal action in Spitsbergen as well). Visitor numbers could be limited, camping on vegetation can be prohibited, waste management etc could be implemented (and is implemented, of course), damaging plants and disturbing wildlife can be (and is) prohibited, minimum distances e.g. to important seabird breeding cliffs could be set etc. etc. there is simply no need to close a fascinating and unique place such as Jan Mayen almost completely down for the public. Those few who actually take the effort to sail up there to have a closer look at some sites for a couple of hours, of even spend some days to climb up Beerenberg.

So, what came with the law no 1456 on November 19, 2010 that is called „Forskrift om fredning av Jan Mayen naturreservat“? The main points are: tourists are not allowed to go ashore or camp within the nature reserve (a strong contrast to the way nature reserves are designed and managed so far in Spitsbergen). The nature reserve comprises the whole island except the station area and a smaller area in Kvalrossbukta. This means effectively: you can land only at Kvalrossbukta or at Båtvika near the station. From there, you are actually allowed to walk anywhere you can, but you are not allowed to camp elsewhere either. As ship-based visitors will usually neither have enough time nor the ability to walk very far, this means that most parts of Jan Mayen are effectively closed off. The official version is (according to hearing documents) that this is not the case: following this version, traffic is not banned, but only „channeled“, as you can actually walk from the two remaining landing sites. But this is practically virtually impossible for most. The island is practically almost completely closed. Full stop.

Finally now the text of the 2010 law. As far as visitors are concerned, relevant parts include the following ones (translation by the current author. No official translation):

Chapter 1 (§§1-3) describes the extent and purpose of the nature reserve.

§ 2 (excerpt):

The „Jan Mayen nature reserve“ includes the whole island except a „business area“ (virksomhetsområde) on the east side of the island (Olonkinbyen (the LORAN station), the weather station and the runway) and a smaller area in Kvalrossbukta on the west side of the island … together with territorial waters except a smaller area at Båtvika (the small bay near the station. Author).

§ 3 Aims (complete translation):

The purpose of the protection is to preserve an almost untouched arctic island and nearby seas, including the sea bottom, with a unique landscape, an active volcanic system, special flora and fauna and many historical remnants, and especially, to protect the following:

- The island’s great and unique landscape

- The island’s peculiar volcanic rocks and landscapes

- The island as an important habitat for seabirds

- The close relationship between marine and terrestrial life

- The special ecology that is developed on isolated islands

- The historical perspective represented by cultural heritage from all main periods of Jan Mayen’s history

- The island and nearby marine area as a reference area for reserach.

(author’s comment: who wouldn’t agree with all the above? Can anyone please tell me how occasional Zodiac landings with tourists walking under supervision by guides within rather limited areas and a few mountaineers hiking up Beerenberg’s glaciated slopes could do any harm to the above-mentioned or any other values?)

Chapter 2 (§4) goes into details regarding what is allowed and what not:

§ 4. Landscape, natural environment, flora, fauna, cultural heritage, traffic and pollution (completely translated):

- Landscape, natural environment and cultural heritage

- No action may be taken that can affect the landscape, natural environment or cultural heritage, including setting up buildings, constructions … removing driftwood … building roads, quays, airfields, use of fishing gear that may damage the sea bottom, drainage or any other way of setting areas dry, drilling, explosions or similar and removal of minerals or oil.

- Nobody may damage, dig out, move, remove, change, cover, hide or deface lose or fast cultural heritage or start action that includes a risk of such taking places.

- The regulations of pt. 1.1 do not restrict the following:

- use of permitted fishing gear at sea except equipment that may cause significant damage to the sea bottom

- necessary maintainance of the existing road between Olonkinbyen/airfield and Kvalrossbukta

- necessary maintainance of the existing road/track between Trongskarkrysset og Gamle Metten

- local use of driftwood for maintainance and heating of existing huts on the island and smaller campfires.

Points 2 and 3 of § 4 are followingly briefly summarized by the author:

Pt. 2 of § 4 deals with flora and fauna, which is protected against all damage, destruction and disturbance of any kind unless caused by legal traffic. No new species of animals or plants, including genetically modified species, may be introduced. Point 2.3 of § 4 specifies exceptions for fishing, which is permitted as specified by relevant Norwegian authorities (fishing and coastal departments) as long as it does not damage the sea bottom.

Pt. 3 of § 4 deals with historical sites. All artefacts and traces from human activity which is older than 1946 is automatically protected. Younger artefacts may also be protected, this is for example the case with Gamle Metten, the station used after WWII. „Protected“ means that everything that might potentially change the artefact and surrounding site is forbidden. Everything means really everything. Period.

Pt. 4 of § 4 (complete):

- Traffic (non-motorized and motorized)

- All traffic shall take place in a way that does not damage or in any way diminish the natural environment or cultural heritage or leads to unnecessary disturbance of animals.

- Putting up tents and camping is only allowed for the station crew and their visitors.

- Landing persons with boats is not allowed inside the nature reserve. The station commander may in special cases give permission to land inside the nature reserve.

- Landings with aircraft is prohibited inside the nature reserve. From April 01 to August 31 it is, beyond necessary traffic to and from business areas, prohibited to fly closer than 1 nautical mile from concentrations of birds or mammals. In the same period, it is prohibited to use a ship’s horn, fire a gun or make any other loud noise within 1 nautical mile from bird colonies.

- Motorized traffic is limited to vehicles that belong to the station and only on tracks and roads marked on the attached map.

- Pts. 1.1 and 4.5 do not restrict use of alternative routes in connection to necessary official traffic („nødvendig nyttekjøring“), if existing roads and tracks as shown on the map cannot be used due to special weather- or wind situations.

- Pt. 4.5 does not restrict traffic with snow mobile or tracked vehicles on frozen and snow-covered ground

- for transporting goods to the station if the weather requires ships to anchor at other places than Båtvika

- for inspection and maintainance of installations

- for transport connected to maintainance and delivery of fuels and provisions to existing huts away from roads

- for getting to the huts during weekends and similar occasions for recreation of the station crew.

- Authorities can prohibit/regulate any traffic in the whole nature reserve or parts of it, if considered necessary to avoid disturbance of wildlife or damage of vegetation or cultural heritage.

Pt. 5 of § 4 deals with pollution, which is obviously mostly prohibited. The remaining §§ (8-12) regulate general dispensations for authorities, administration, sanctions (fines or imprisonment up to 1 year) and implementation (immediately on November 19, 2010). Maps attached.

Chapter III (§§5-6) deals with excemptions, which are given to, for example, authorities including police, military and rescue services. Permission to move around etc. can also be given in special cases for scientific or other reasons.

Chapter IV (§§7-9) specifies administrative aspects including competence etc.

Chapter V (§§10-12) makes sure you will be given a hard time if you break the regulations (fine or imprisonment up to 1 year) and puts the law into force on November 19, 2010.

copyright: Rolf Stange